By Jeff Vircoe

As Canadians pause this week to remember the battle of Vimy Ridge and its impact on a wide-eyed, impressionable nation 100 years ago, it may surprise some in recovery, from their own battles with the bottle, to learn that one of the most sage bits of advice offered to them has a close connection to the war “over there.”

One of the most enduring slogans of Alcoholics Anonymous is Live and Let Live. Found in the organization’s basic text book, the title from which the name of the fellowship originated, Live and Let Live is one of the big three slogans, sandwiched between First Things First and Easy Does It in the chapter The Family Afterward in all four editions of the Big Book.

Its meaning is not vigorously debated. Most would agree that Live and Let Live fits along the lines of “mind your own business”, “let sleeping dogs lie”, or my personal favourite, “What people think of me is none of my business.”

“We try not to indulge in cynicism over the state of the nations, nor do we carry the world’s troubles on our shoulders,” wrote A.A. co-founder and Big Book author, Bill Wilson, in the chapter in which Live and Let Live appears.

Practical. Sage. Innocuous advice, perhaps.

In early April 2017, as we solemnly watch rickety black and white images of young men racing up steep trench walls and out into Vimy’s no man’s land pockmarked with millions of shell craters, the juxtaposition of the peaceful concepts behind Live and Let Live and any military connection may seem polar opposites, yet the battlefields are precisely where the term originated.

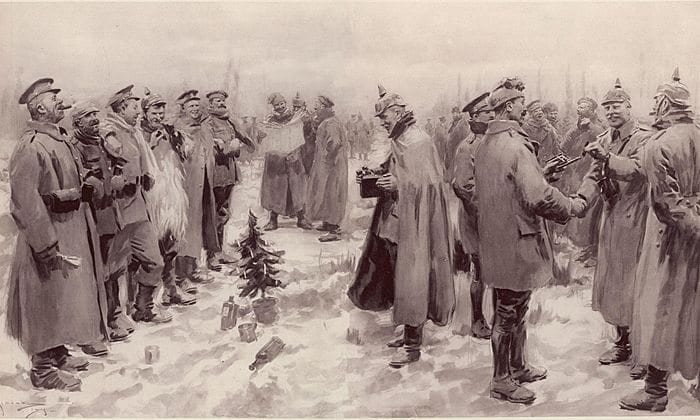

In a series of unofficial, but widespread, ceasefires on the Western Front around Christmas 1914, French, German and British soldiers laid down their weapons, crossed the trenches and created a sense of fellowship with one another. There were reports of joint burial ceremonies and exchanges of food and souvenirs. Harmless soccer games broke out. These spontaneous mini-truces broke up the horror and monotony of steady shelling and sniping, attacks and counter attacks. The truces meant, literally, that the soldiers would stay alive – Live, and would allow the other side to stay alive, as well – Let Live.

The New York Times and Britain’s Daily Mirror and Daily Sketch newspapers published reports of the examples of good faith exhibited by those warriors, but as senior commanders on both sides learned of the fraternization on the front lines, orders were given to knock it off. Some units defied the no fraternization order over the next year, especially around seasonal holidays like Easter and Thanksgiving, but by 1916, with gas attacks and casualties continuing to climb into the hundreds of thousands, the war bogged down, resentments hardened and Live and Let Live was put on hold as far as the battlefields went.

In his book, Trench Warfare 1914-1918: The Live and Let Live System, British author Tony Ashworth went through diaries, letters and veterans’ testimonies and came to the conclusion that the term and concept of Live and Let Live was widely known by that generation.

These days, when you think about sayings like, “Pick your battles” or “I’m not willing to die on this hill”, you can see the potential military correlation. Not necessarily so with “Live and Let Live.”

It may be important to remember that, in 1939, the Big Book was introduced to a world only 20 years removed from the supposed War to End All Wars, or The Great War, as World War One was known by that generation. Much of the lexicon of the day still held a military connection. In fact, many in the 12 Step movement were veterans of WW1.

Bill Wilson was part of the Vermont National Guard, having had his first drink after being commissioned as an artillery officer.

“I found the elixir of life,” he wrote in Pass It On. “Even that first evening I got thoroughly drunk, and within the next time or two I passed out completely. But as everyone drank hard, not too much was made of that.”

Neuro-Psychiatrist Dr. William Silkworth, the physician in charge of Towns Hospital in New York City where Wilson detoxed, served in the U.S. Army from 1917-1919. Rowland Hazard, who brought Ebby Thatcher to the Oxford Group before Ebby introduced Wilson to that organization from which A.A. evolved, had been a Captain in the U.S. Army Chemical Warfare Corps. And Jim B., an agnostic A.A. pioneer who is credited with establishing the Third Tradition, the only requirement for membership is a desire to stop drinking, and the terms, “God As We Understand Him” and “Power Greater Than Ourselves” rather than religious terminology, was a first class private in the U.S. Army in the First World War. His story, The Vicious Cycle, was published in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th editions of the Big Book.

With all these veterans having input into the Big Book as Wilson cobbled it together through most of 1938, it is no small wonder that Live and Let Live, a military term urging alcoholics to put their own psychological weapons of mass destruction down, came to pass.

Photo: An artist’s impression from The Illustrated London News of January 9, 1915: “British and German Soldiers Arm-in-Arm Exchanging Headgear: A Christmas Truce between Opposing Trenches”